A SAILOR'S ORDERS

It all begins with a distress call, a voice on the radio crackling the coordinates, the description of the three vessels and the number of people on board, 277. The captain contacts Frontex to get directions on where to disembark these people, meanwhile setting a course to intercept the drifting vessels.

It all begins with a distress call, a voice on the radio crackling the coordinates, the description of the three vessels and the number of people on board, 277. The captain contacts Frontex to get directions on where to disembark these people, meanwhile setting a course to intercept the drifting vessels.

It's night on that stretch of the Mediterranean, halfway between Libya and Sicily, and the horizon of the sea is distinguished from that of the sky only by the myriad of stars and the moon.

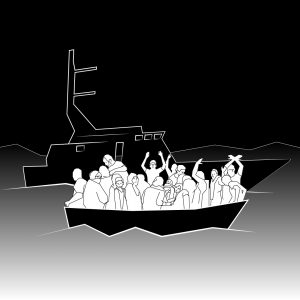

When the Italian Navy patrol boat approaches the three half-submerged rubber dinghies, it is greeted by cries of hope: hundreds of people, young and old, waist-deep in water, waving, trembling, begging for help, calling out, crying. In the sea, besides the sinking rubber dinghies, float the bodies of those who didn't make it, colorful fragments of shattered families adrift in the darkness of a sea of suffering. For those whose lives are in danger, those uniforms represent safety, friendship, hope of salvation, and the end of their Homeric, nightmarish journey. The memory of the horrors that every human being on those vessels had to endure to leave Africa will remain etched in their bodies and minds for a long time to come, but with Italy's arrival, the worst is over. The Italian sailors emerge from the patrol boat like angels illuminated by the floodlights that cut through the night, already at work with life jackets and ropes to rescue the shipwrecked.

It seems like a rescue operation like so many others carried out by the Italian Navy, but the rescuers know the reality is different, and their hearts are in a vice as they welcome aboard those 277 souls, those children, those men, women, and elderly people who continue to ask them for information and reassurance. There's Shara, a Nigerian, holding her two-year-old child in her arms; her sister Fatima, pregnant at seventeen, caresses her belly. Neither of the two children, neither the one on the boat nor the one about to be born, has a clear father. They are the children of Libyan rapists, the tormentors who exploited and raped the two girls for two years, but that past is now behind them. "We made it, we reached Europe," Shara says tearfully to her son, and looks at the Italian sailor beside them, seeking confirmation in his eyes.

The grip on the sailor's heart tightens further. "Don't worry, we'll take you to Italy," he lies, but at dawn the deception is evident in the lights of Tripoli's port, the signs in Arabic, the soldiers waiting on the dock. After everything they've been through, they've brought them back to their starting point, gathered them, fed them, and deceived them before returning them to the clutches of their captors. The protests and pleas begin. Now the migrants call the Italians brothers. "Brothers, why are you doing this to us? Why, after saving us, do you take us back to hell?" Oluwa, a giant of a man, kneels before the Italian sailor, torn between duty and morality. Fatima also pleads, pointing to the child she carries in her womb. "Do you understand that this child is the son of those Libyan torturers who raped me for months, and who will rape me again as soon as you let me disembark?" The sailor's eyes fill with tears as he curses his orders, measuring the depth of his guilt with the yardstick of his patriotic duty, for beneath that military uniform lies a man, a father, and a husband who can no longer discern the limit, the boundary: where to draw the line between duty and morality? How can one remain human under these circumstances?

No Contracting State shall expel or return (refoulement) a refugee in any manner whatsoever to the frontiers of territories where his life or freedom would be threatened on account of his race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion.

Geneva Convention – Article 33

“I’m ashamed and I can’t sleep at night,” the soldier says. “There were about forty women on board, many pregnant, many with very small children, and I, who had saved them, had to bring them back. […].”

This man carried out an order even though he didn't think it was right. Would we really have acted differently in the same circumstances? Perhaps by challenging the order to our superiors on the basis of the Geneva Convention?

There's no point in assigning blame here; there is responsibility, and it weighs on many countries and many people. However, it's necessary to define what it means to remain faithful to one's morality within a rigid hierarchy like that of the authorities. Must we really always follow hierarchical orders? During humanitarian crises like these, the line between morality and duty becomes blurred, complicated, and filled with bureaucracy. In this chaos, it's easy to lose sight of fundamental values like human rights. The problem is that if we forget this in situations like these, if we follow orders, people die or are tortured. These are those difficult choices, which have occurred countless times throughout history, where both options seem wrong and our morality is the only deciding factor.