THE WOMAN WHO MAKES THE WALLS SING – SHAMSIA HASSANI

The news of the Taliban's return to power in Afghanistan has shocked the entire world and generated diverse reactions on all fronts, from the political and military to the humanitarian and legal. After all, it couldn't be otherwise when a twenty-year chapter in history closes, when an era ends and we look to the future with uncertainty, fear, and hope. Events of this magnitude cannot fail to leave their mark on art, which is perhaps more capable of expressing the great changes underway than many other means of expression. Since this summer, one artist in particular has been thrust into the spotlight, along with her works, which have spread widely online and become a symbol of what is happening in Afghanistan.

The news of the Taliban's return to power in Afghanistan has shocked the entire world and generated diverse reactions on all fronts, from the political and military to the humanitarian and legal. After all, it couldn't be otherwise when a twenty-year chapter in history closes, when an era ends and we look to the future with uncertainty, fear, and hope. Events of this magnitude cannot fail to leave their mark on art, which is perhaps more capable of expressing the great changes underway than many other means of expression. Since this summer, one artist in particular has been thrust into the spotlight, along with her works, which have spread widely online and become a symbol of what is happening in Afghanistan.

I want to cover with colors all the bad memories of the war in people's minds

– Shamsia Hassani –

Umm-ul-banin Shamsia Hassani, born in 1988 in Tehran, Iran, to an Afghan couple from Kandahar, returned to Kabul in 2005 to study, work, and paint. Not that Shamsia was unknown before August; in fact, her works have been circulating around the world for ten years, ever since she learned the art of graffiti from the English street artist Chu during a workshop (held by Combat Communication) in Kabul in 2010.

Shamsia has always loved art and painting since she was a child, but she didn't have the freedom to pursue this passion. She was able to start painting only after being accepted into the Faculty of Fine Arts at Kabul University. Graffiti opened up a whole new world for her. First of all, stencils and spray paint are cheaper than paint and brushes, and secondly, graffiti can be done anywhere, so the canvases are practically endless.

Shamsia at work on a wall in Kabul

Graffiti, above all, is an art form that, in a country lacking art galleries and exhibitions, is much more effective in reaching people, as it can be displayed anywhere in the urban fabric, on the walls of homes and factories. Graffiti wants to be seen, shouting its message to everyone from the streets. In Shamsia's case, it concerns the importance of women's role in civil society and institutions, upholding the values of peace, solidarity, and freedom of creative expression for the entire world.

Through her work, Hassani hopes to present a different Afghanistan, one not automatically associated with war and violence but with beauty and art, and perhaps she's succeeding. With the help of her husband, a theater director and videographer, her works have been published online, and thanks to this visibility, she's invited around the world to present her work and paint murals.

United States, Italy, Germany, India, Vietnam, Switzerland, Denmark, Norway and other countries.

Her art is her weapon, her heart is the engine that drives her to fight. Shamsia Hassani is a woman who, in her fight against oppression, has chosen to remain human.

The arts are society's rainforests. They produce the oxygen of freedom, and they are the first alarm system to go off when freedom is in danger.

– June Wayne –

Twenty years ago, in Italy, graffiti wasn't recognized as art by civil society, and most of the time, those seen painting it were considered vandals. What does it mean, however, to be a street artist in a deeply conservative country like Afghanistan, painting murals in the historic center of Kabul, exposing yourself to the public eye in acts considered idolatrous and in ways so different from those imposed by patriarchal traditions, if you're a woman? A lot of talent, no doubt, and even more courage, because every noise raises alarm, every whistle chills the blood, every insult is a stone hurled at your dignity.

Making art in Afghanistan requires a thick skin, to avoid giving in to the threats of fundamentalists, and fast legs, to escape reprisals from armed gangs and car bombs, threats that are still real, daily: just last June, two young artists died in an attack in Kabul while returning home. Making art was frowned upon even before the Taliban, but it was possible. Shamsia herself reminds us:

Art was evolving. The number of artists and art lovers was gradually growing. Of course, there were still many who opposed art, but it was available to everyone, and we had the freedom to be artists.

– S. H. –

Shamsia has repeatedly received threats, both for her artistic activity as a street artist and for her teaching activity as an associate professor of sculpture at Kabul University, both of which are equally irreconcilable with the forced moralization imposed by the Taliban on Afghan society.

She was forced to give up teaching; she was faced with the choice of giving up painting or continuing to practice it for as long as she wished on the crumbling walls of a squalid prison.

But Shamsia refused to compromise the principles she had dedicated her entire life to defending, accepting the pain of exile and the destruction of her message of pride and hope. She would continue her resistance on the other side of the mountains, with the same indomitable spirit that would have inspired, at different times but in similar circumstances, the same choice to resist cruelty until her last breath.

Thus, on August 24, through her social media profile, in regret and suffering, she communicated her courageous choice to remain true to herself, to remain human.

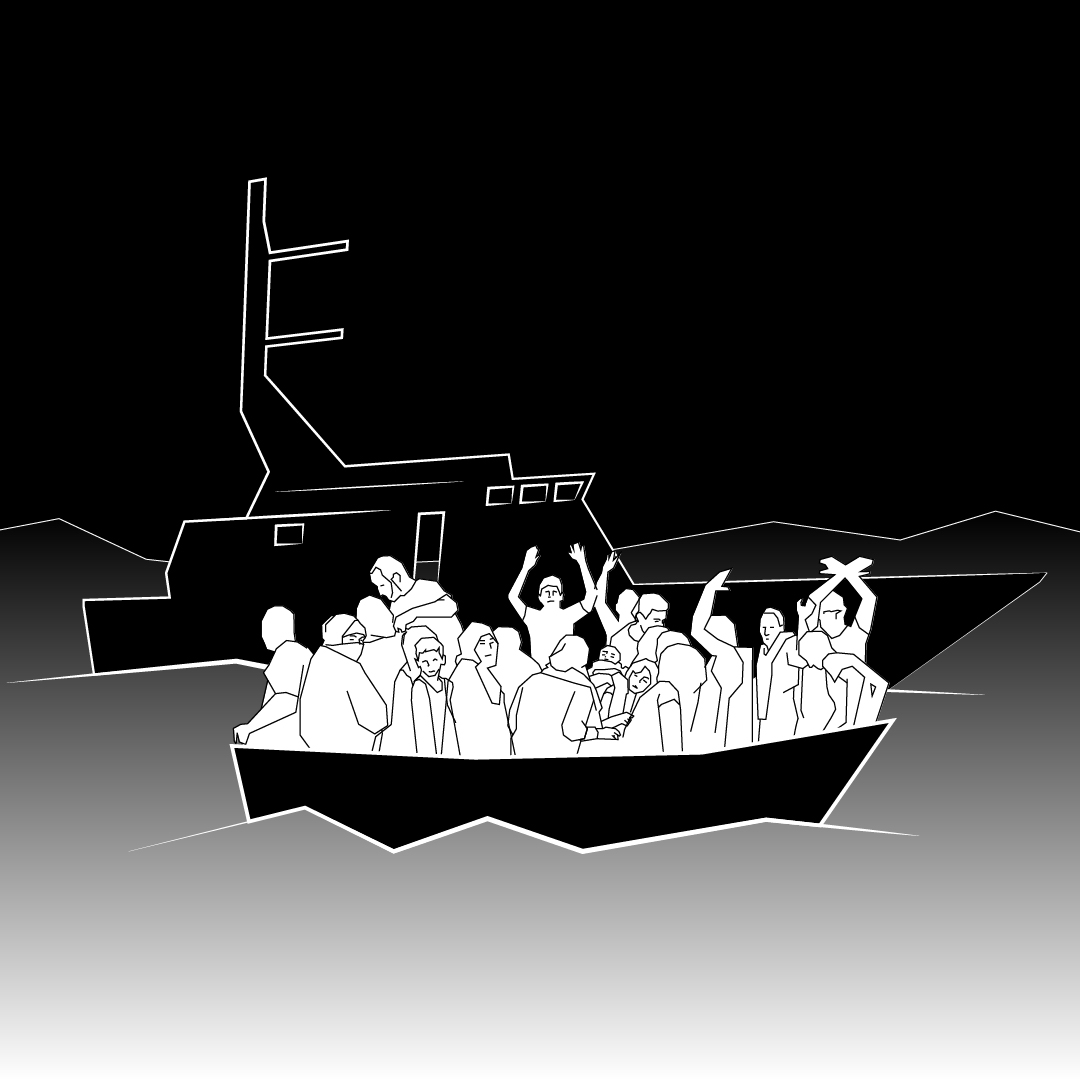

His art, which also encompasses digital projects such as Dreaming Graffiti and Birds of No Nation, speaks the voice of the many young people forced to make the same choice as him, in an endless exodus that has been emptying Afghanistan since the 1980s, depriving the country of intellectual forces with which to counter the Taliban's single-minded way of thinking, condemning it to inexorable decline.

Dreaming Graffiti

Birds of No Nation

I feel that my artworks are visual alphabets that connect to people through their mental visual alphabet

– Shamsia Hassani –

Although rich in meaning and color, enough to capture the eye of the casual observer as well as that of the connoisseur, Shamsia Hassani's works are characterized above all by a precise symbolism, which has given rise to diverse interpretations and even more numerous controversies.

We don't think it's fair, either towards our readers or the author herself, to discuss the civic value of Shamsia's work without sharing our opinion regarding the controversies we've mentioned, which see Hassani's works as little more than colorful crocodile tears.

Because the artist paints veiled women, sometimes even wearing burkas, she has ended up being associated with the same cultural trend as the Taliban, or at least considered, with indignation, a revolutionary who is not revolutionary enough.

Now, however right E. Degas may have been when he said that "art is not what you see, but what you make others see," it's equally true that when you possess the key to understanding a work, the entire experience of contemplation changes. In Hassani's case, she herself explains the meaning behind her works:

My paintings have a character – just like characters who play roles in movies, the characters in my paintings also play different roles. This character (the female subject of her works, editor's note) plays the role of a human being, but since I am a woman, I can understand women better, and women have more restrictions than men in our society, so I decided that my character was a woman. A woman with closed eyes and no mouth, with deformed musical instruments that give her power and self-confidence to play her voice. Her closed eyes mean there is nothing good to see – she would like to ignore everything, to suffer less. My works are mainly focused on individuals and social issues, but sometimes they become political. The protagonist of my paintings plays different roles: sometimes she is a fighter, while other times she is a refugee with no future. Sometimes she seeks peace and sometimes she represents someone without an identity. Sometimes she is lost in her dreams while sometimes she is lost in pain and suffering; she struggles with the past and the future, and then she is a patriot who loves his homeland and fights despair.”

– S.H. –

In Hassani's works, therefore, we see women because they speak first and foremost of women, of their difficult lives in a deeply conservative and patriarchal country like Afghanistan. But the messages her symbols convey are simply human, both in the eyes of those who are women and those who, like the writer, are not.

In addition to the closed eyes (what I want to see does not exist, and what I can see is horrible), the absence of a mouth (nobody cares what I have to say; the mouth is of no use to a woman in the cage that the Taliban have built), the broad shoulders (to see women in society in another way, strong, full of movement and free to be happy), the musical instruments (they are a powerful symbol that represent the ability to express oneself freely, despite the absence of words), there is another symbol that needs to be clarified: the burqa and chador with which Shamsia represents this woman have been the cause of misunderstandings.

The artist has already been accused of supporting the use of the burqa as a tool for oppressing women. This simplistic and presumptuous view, with which we Westerners like to judge the customs of the Near and Far East, is hardly the best perspective from which to view Hassani's work. Indeed, the veil in her drawings is not at all opaque, but transparent, revealing the strength and humanity of the woman beneath. Furthermore, as the artist herself states, the issue is not the burqa, nor is it the fight against: in fundamentalist Islamic theocracies like Afghanistan, even without the burqa, women certainly do not gain more rights, more dignity, more freedom, and more respect in society. Shamsia does not believe that burning a garment can bring about change; instead, she believes that women's education should be the primary tool, the right path to achieving women's emancipation and the achievement of those rights that should be guaranteed to all human beings.