A KICK TO HATE – PREDRAG PASIC

Imagine waking up in your bed to the sound of your alarm clock, the call to your usual daily routine: you make coffee, freshen up in the bathroom, and have breakfast while watching the sun rise over the buildings of your city. A new day begins, you leave the house and, like every morning, greet your neighbor on the steps of your apartment building. You go out into the street with the day's upcoming events and commitments in your mind: going to work, stopping by the supermarket, visiting your parents or friends.

Imagine waking up in your bed to the sound of your alarm clock, the call to your usual daily routine: you make coffee, freshen up in the bathroom, and have breakfast while watching the sun rise over the buildings of your city. A new day begins, you leave the house and, like every morning, greet your neighbor on the steps of your apartment building. You go out into the street with the day's upcoming events and commitments in your mind: going to work, stopping by the supermarket, visiting your parents or friends.

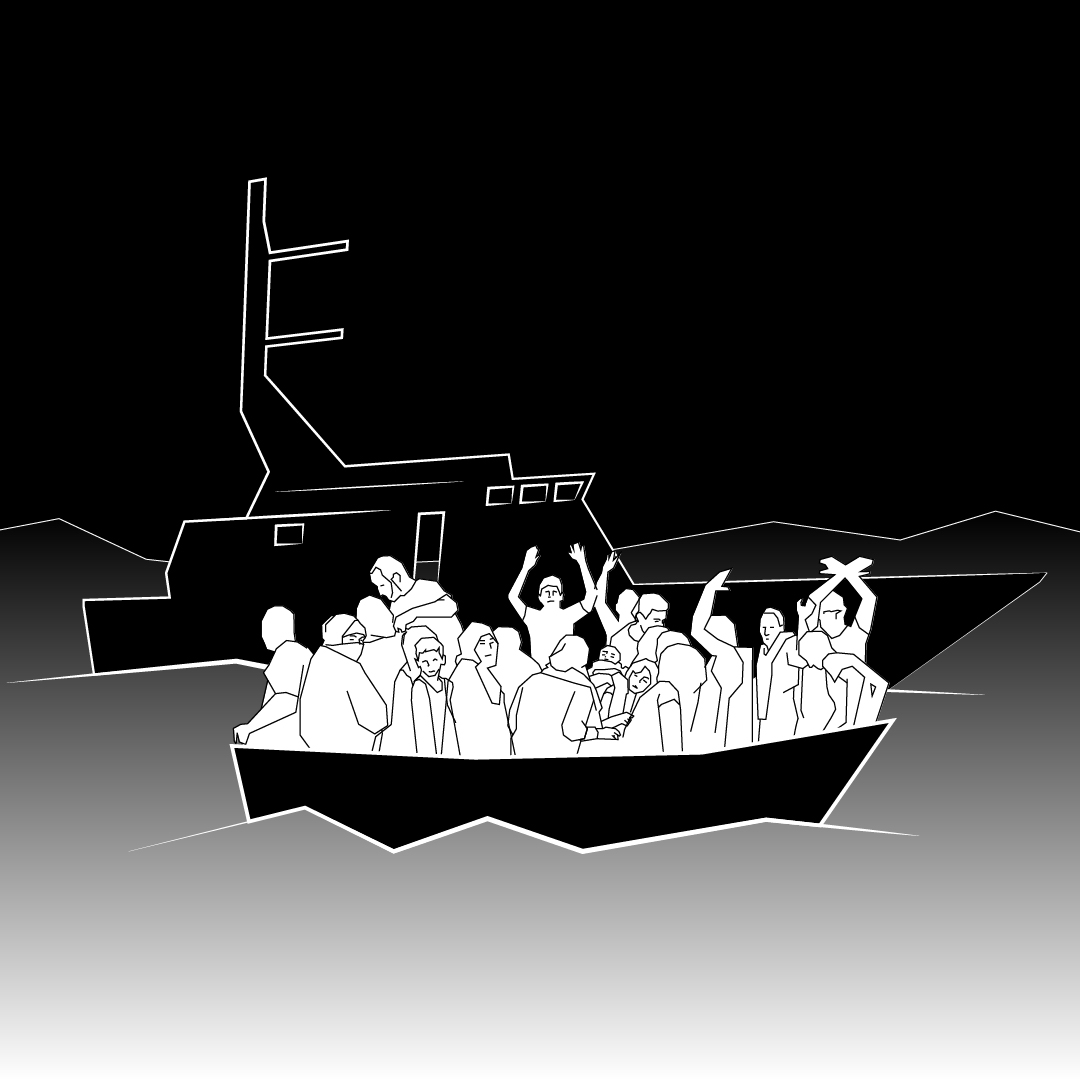

Now imagine your alarm clock is the dry thunder of Kalashnikov rifle fire in the street: a reminder of your usual daily routine. Imagine you have no coffee, no food for breakfast; most of your city's buildings are still there, but dawn is filled with tension. Imagine one of your fellow citizens is literally willing to kill you for a cigarette; that to get around the street you have to run, praying that the sniper on duty doesn't aim in your direction or that a grenade doesn't rain down on you from the sky; try to imagine your neighbor, the same one you greeted every morning on the stairs, barging into your house with a rifle in his hand and shouting, "Get out of my way, you Muslim bastard."

What you're imagining is a Sarajevo morning in the early 1990s; a city filled with hatred and death, where the smell of blood had replaced the aroma of freshly baked bread and the city market, where the cries of victims and executioners drowned out the muezzin's call at dawn.

Sarajevo, once a centuries-old symbol of multi-ethnic coexistence, became the sad stage of one of the most atrocious and senseless wars of the twentieth century.

Now, on a morning like any other, you turn on the radio, thanking heaven you're still alive and preparing to listen to the now customary obituary of the day's deceased. But at a certain point, the announcer's voice is interrupted by a sort of commercial:

“PREDRAG PASIC OPENS A FOOTBALL SCHOOL FOR ALL THE CHILDREN OF SARAJEVO.”

A soccer school? IN SARAJEVO? You'd think it was a joke; it would be crazy. Yet you've heard that voice before, long ago, in days that now seem distant, when Sarajevo was a paragon of cultural and religious integration. It's the voice of Predrag Pasic, a name that until just a few years ago made the hearts of thousands of soccer fans in the Balkans skip a beat. A famous midfielder for the Yugoslav national team, he returned to his hometown a few years ago after a football career in Germany.

Pasic decides to return to wear the jersey of his favorite team: FK Sarajevo. When the war broke out in 1992, he was still a playing footballer and had to decide what to do. He could have gone abroad, hoping to secure a contract with a team interested in him. Instead, he decides to stay.

One morning, sitting drinking coffee with his old teammates during a rare ceasefire, Predrag looks out over his city, a city that, due to the war, has become a shadow of its former self:

The buildings are defaced by bombs, many of them no longer exist, there is no trace of what could be considered normal life, but above all, there are no children playing in the streets. And it is precisely in a ghost town that Predrag decides to open a soccer school for children. He wants to help them play again, to give a semblance of normality to their existence, to teach them that life goes on despite everything, but, most importantly, to spread the message that the soul of Sarajevo can only be saved by putting hatred aside and that people can once again see themselves not as Serbs, Croats, or Muslims, but as one great team. Just like that FK Sarajevo imprinted on his heart.

For many, the idea of opening a soccer school in a city besieged by bombs and with its residents targeted by snipers is simply "madness." But Pasic persists, gathers together some of the FK players, contacts the only radio station still active in the city, and records the famous message. Thus, the BUBAMARA soccer school is born, near a cemetery that used to be a soccer field.

On opening day, no one expected more than six or seven children. Imagine the surprise of those few who believed that "crazy Pasic" when over two hundred children showed up at the camp. Serbian, Muslim, and Croatian children, ready to play together, to team up while their parents gave in to hatred and fear.

Predrag makes things clear right from the start: he wants the school to be a meeting place, he doesn't want to hear about nationalism: "No walls, only bridges," he loves to repeat.

Bridges. The symbol of Sarajevo.

Like the one in Grbavica that unites the city.

Bridges.

Like the one children have to cross every time they get to the sports center.

And for once, in this story, the snipers don't shoot.

“I have always thought that integration was a value”

Today, years later, many say that that madman FK was right.

Twenty-five years later, the school is still there, proving that remaining human is possible and that even a simple sport can save lives, demonstrating the alternative of integration when hatred and discrimination reign supreme. Bubamara now has several schools across the country, places where kids get to know each other, learn to accept their differences, and play together. All equal. "And the best part is that it happens to their parents, too," Pasic says in an interview. "It seems trivial, but it's incredibly important in this country. Getting to know others, traveling, and not just being stuck in stereotypes."

During the war years, some children managed to reach Italy and, thanks to the INTERCAMPUS project, had the opportunity to do internships in the youth of Italian teams.

The greatest satisfaction for Pasic, however, has always been seeing them play as one great team.

Over the years, at Bubamara, I've seen thousands of extraordinary kids. Over time, they've become doctors, teachers, and lawyers. I like to think, sometimes, that I've helped them bring out the best in themselves.